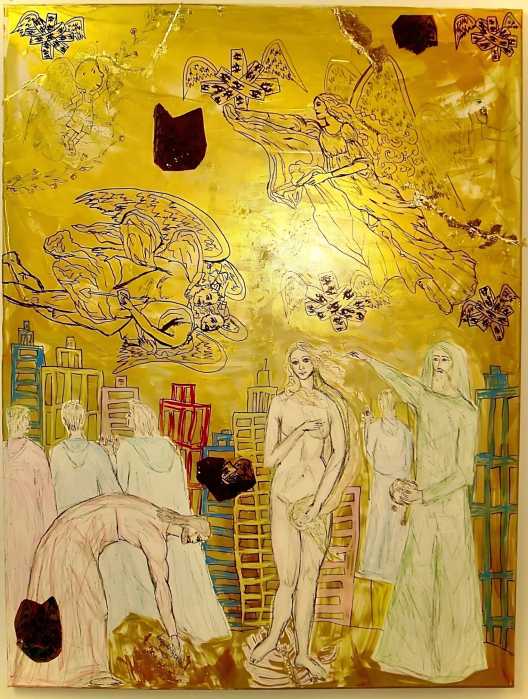

The world Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney inhabited was elegant—yet terrifying. Beneath the satin gloves and glittering salons, the social order was enforced like a corset: laced tight, leaving little room to breathe, let alone create.

It was an age of performative femininity, inherited power, and velvet submission. For a woman of her standing, the expectations were crystalline—delicate, perfect, and sharp enough to cut through the spirit.

To break from that mold required something more than rebellion. It required magic. Diamonds are not born—they are formed under pressure. Gertrude, heir to the Gilded Age’s most gilded name, transformed that pressure into legacy.

The 1916 portrait of Whitney by Robert Henri, hanging now in the very museum she founded, does not merely depict this transformation. It documents it. This is not the portrait of a lady—it is a rupture.

Henri, famed leader of the Ashcan School and defender of grit over gloss, was never seduced by aristocratic ease. His work was built on blood, labor, and the piercing honesty of character. In Gertrude, he found a subject who did not need polishing. She needed witnessing.

Gone are the corsets, the jewels, the stiff postures of propriety. Instead, Henri offers something rare: a woman of unimaginable wealth slouched comfortably in what appear to be silk pajamas, eyes half-daring, half-amused, mouth slightly curled in what can only be described as a devil-may-care smirk. Her hair is unfussed, her hands relaxed, her body at ease in a way that defies the weight of her name. This was no accident. It was iconoclasm.

In an era when female power was often hidden behind painted smiles and decorative restraint, this portrait crackles with sovereign nonchalance. The confidence is not performative. It is innate. Her attire, loose and intimate, reads like a subtle threat to convention. She is not armored in pearls. She is armed with self-possession. The power on this canvas is not derivative or borrowed. It emanates. It makes clear that Whitney did not need approval.

She required space.

As a sculptor, Gertrude understood the architecture of form. She knew how to carve. She also knew how to be carved. This portrait is collaboration, not control. Henri does not reduce her to muse or matron. He elevates her to monument. He paints her not as society wished to see her, but as she was—and perhaps more provocatively, as she wanted to be seen.

This is the radical potential of portraiture. It freezes power in the act of becoming. It renders invisible revolutions visible. In this case, it immortalizes a woman who used her position not to preserve a system, but to subvert it. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was not content to simply collect art. She created it, funded it, and fought for it. Her patronage was not passive. It was visionary, muscular, unapologetically American. She made space for the modern when modernism was still considered vulgar. She gave the new world a museum of its own.

To stand before this painting is to witness not just Gertrude’s image, but her refusal to disappear into history’s background. The portrait becomes a kind of portal: to the salons she disrupted, the careers she launched, the institutions she challenged. Henri captured her just as she was transforming from woman to institution—a human force preparing to house an entire movement.

In the Whitney Museum, this portrait hangs not as ornament, but as origin story. It reminds us that art is not just beauty. It is biography. It records who we dared to be, who we chose to see, and what we refused to forget. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was not the subject of this painting. She was its co-conspirator.

Through this act, she gave us more than a museum. She gave us proof that representation is power—that to be painted truthfully, in defiance of expectation, is to claim authorship of one’s own myth.

For more reflections on art, rebellion, and the radical act of being seen, visit avalonashley.com—a portal for those who understand that culture is not inherited. It is built.