Since the overhaul of the city charter in 1989, the New York City Council has been the presumptive final arbiter of whether a zoning change is enacted under the uniform land use review procedure or ULURP. Recent events highlight why that may not have been the case and why it may not be in the future.

Facing an unprecedented tight and expensive housing market, a growing consensus has focused on inducing development. While supported by many in the abstract, implementation is constrained by local opposition in some neighborhoods.

Private zoning applications face an uncertain path as the council has a tradition of deferring to the council member who represents the impacted area for a thumbs up or thumbs down. After all, each member presumably knows what’s best for the communities they represent, or at least what’s politically palatable. Moreover, members expect reciprocity if they back a colleague should the need arise in their own backyard.

Most typically, members use the threat of opposition to cajole concessions from the developer, with the encouragement of the council speaker, who is looking to both address citywide needs and protect the reputation of the council from charges of arbitrariness and NIMBYism. The upshot is that most projects that make it to the final stage of review are approved in some form, while some are withdrawn at the last moment and a rare number are approved over the objection of the local member.

Against this background, Mayor Eric Adams appointed a charter reform commission last year specifically charged with making recommendations to speed up housing production. They have now finalized their recommendations to be presented to the voters this November.

Several of these are intended to address procedural bottle necks, but three in particular are aimed at member deference.

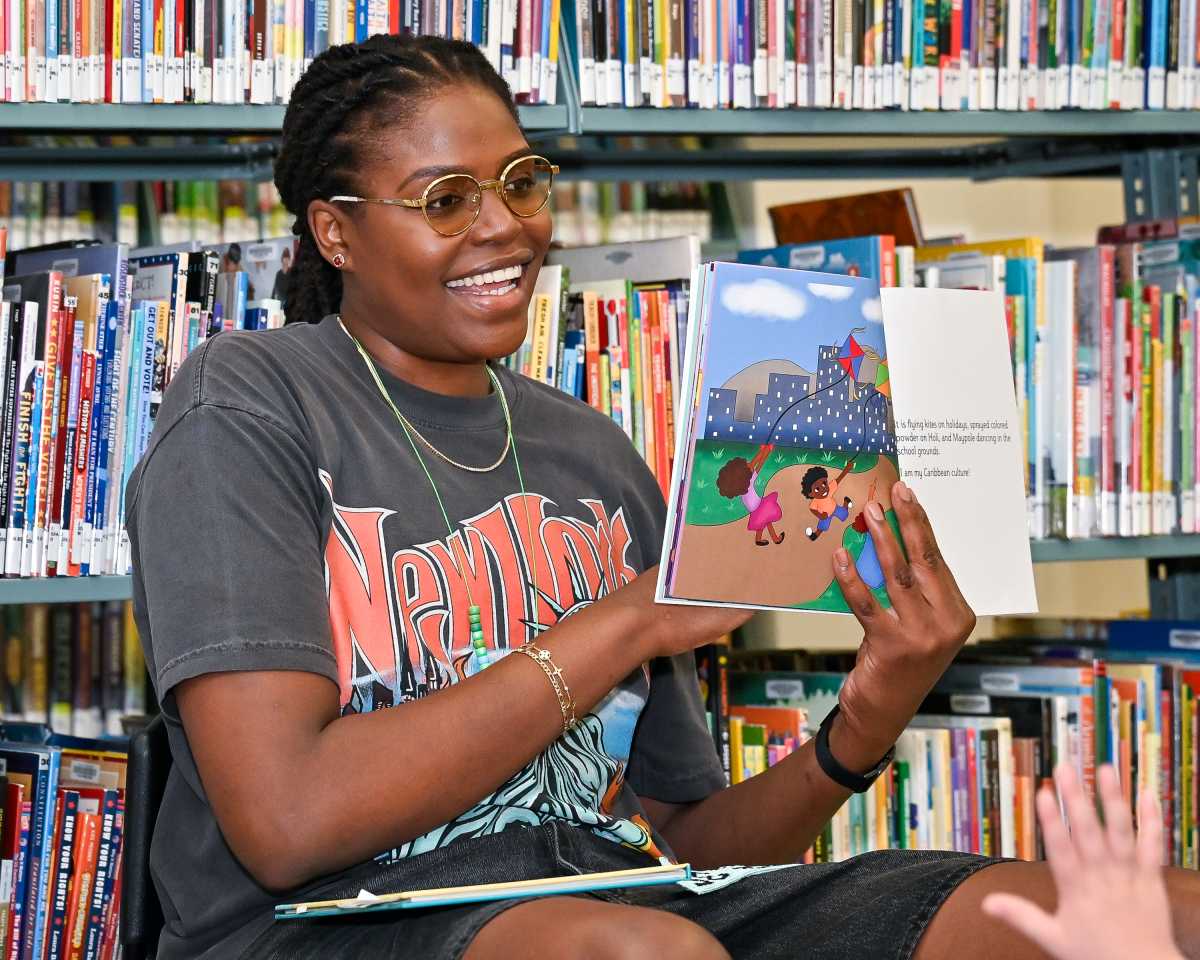

One would take the approval of publicly financed low income housing, euphemistically called affordable housing, out of review by any elected body. Rather, projects sponsored by non-profit organizations would be eligible for a simplified hearing by the Board of Standards & Appeals, the members of which are all appointed by the mayor which currently hears hardship cases. The concept is modeled on the board doctrine of granting variances to nonprofit organizations for program expansion, for example a school whose enrollment has increased and needs a larger building.

Only a small subset of projects will be eligible for this procedure. Larger, more complex and privately financed applications will still be subject to council review.

A sharp departure from current practice would be creation of a new affordable housing appeals board, comprised of the borough president of the affected borough, the speaker of the city council, and the mayor. It would have the power to overrule council disapproval of an application if two of the three members agreed.

In theory, both citywide and boroughwide perspectives would be considered, with the speaker representing both a citywide view and that of the member in whose district the project was located, and who presumably orchestrated its disapproval. It is unclear whether the proposers believe that a speaker would ever vote to overrule a disapproval that likely could have prevented the speaker strong-arming members into approving notwithstanding the local member’s opposition.

It would replace a power that many didn’t even know existed: the ability of the mayor to approve a zoning action by vetoing the council’s resolution to disapprove, itself subject to reversal by a two thirds vote of the council. Even many zoning veterans are hard pressed to remember an instance where this had occurred.

While Mayor Adams hasn’t used this power on any housing application to my knowledge, he was urged to consider it to resurrect the eligibility of Bally’s golf course in the Bronx to win one of the casino licenses in New York City. Bally’s proposal needed local zoning to even be in consideration. But the local council member rallied her colleagues against it and the council voted it down 28-9.

Thus, the availability of this procedure is now out in the open, to be compared to the affordable housing appeals board being proposed.

Should the voters approve, history may echo. The reason the charter was changed in 1989 was because the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the scheme then in effect was unconstitutional. Zoning changes went before the inaptly named board of estimate, which consisted of the three citywide elected officials and the five borough presidents. This was a violation of the principle of “one man one vote” in the sense that the members represented uneven numbers of voters. For example, the vote of the borough president of Staten Island, the city’s least populated, was equal to the vote of the more populous Brooklyn bp.

Under the new regime, the vote of the speaker, who is selected by the entire council but elected to public office only by the voters in one of 51 council districts, has the same vote as a borough president, themselves elected by fewer voters than the mayor. Presumably the drafters took this into account. If successfully challenged, look for the next charter commission.

Former NYC Council Member Ken Fisher is a member of the national law firm of Cozen O’Connor. His practice concentrates on city and state government regulations, transactions and investigations.